Tax-Benefit Models

Where we’re going

We’ve covered a lot of ground quite fast: summary statistics, large sample datasets, data weighting, measuring poverty and inequality, measures of well-being, tax incidence and incentives. Now we’ll to put all these things to use and build a microsimulation tax-benefit model.

Building a tax-benefit model

In essence a tax benefit model is a simple thing. It’s a computer program that calculates the effects of possible changes to the fiscal system on a sample of households. We take each of the households in our dataset, calculate how much tax the household members are liable for under some proposed tax and benefit regime, and how much benefits they are entitled to, and add add up the results. If the sample is representative of the population, and the modelling sufficiently accurate, the model can then tell you, for example, the net costs of the proposals, the numbers who are made better or worse off, the effective tax rates faced by individuals, the numbers taken in and out of poverty by some change, and much else.

The model we use here is written in the Julia programming language1. All the program code stored on a public website2 but there’s no need to look at that unless you’re interested. We’ve equipped the model with a simple Web interface so that you can interact with it.

Structure

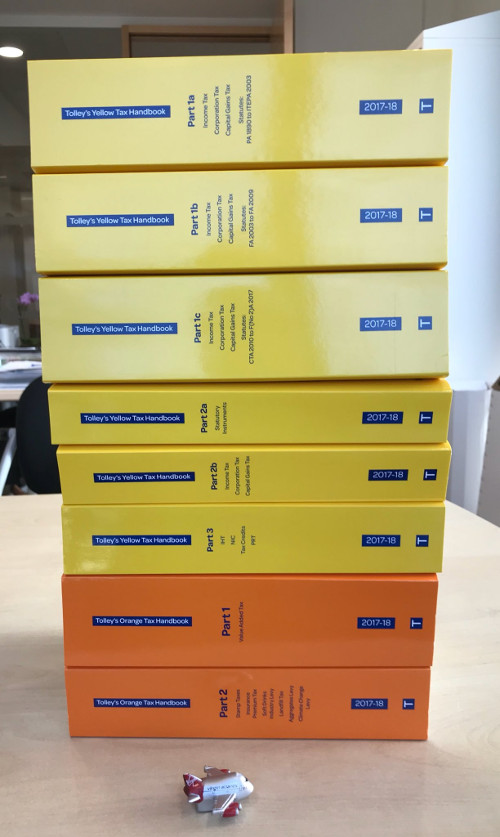

The main thing we haven’t covered already is how we actually do the tax and benefit calculations. The first thing to confront is that there’s a lot of stuff to model: the standard guide to the UK tax system is Tolley’s Guides3. Here are the current Tolley’s guides:

(Source:4)

(Source:4)

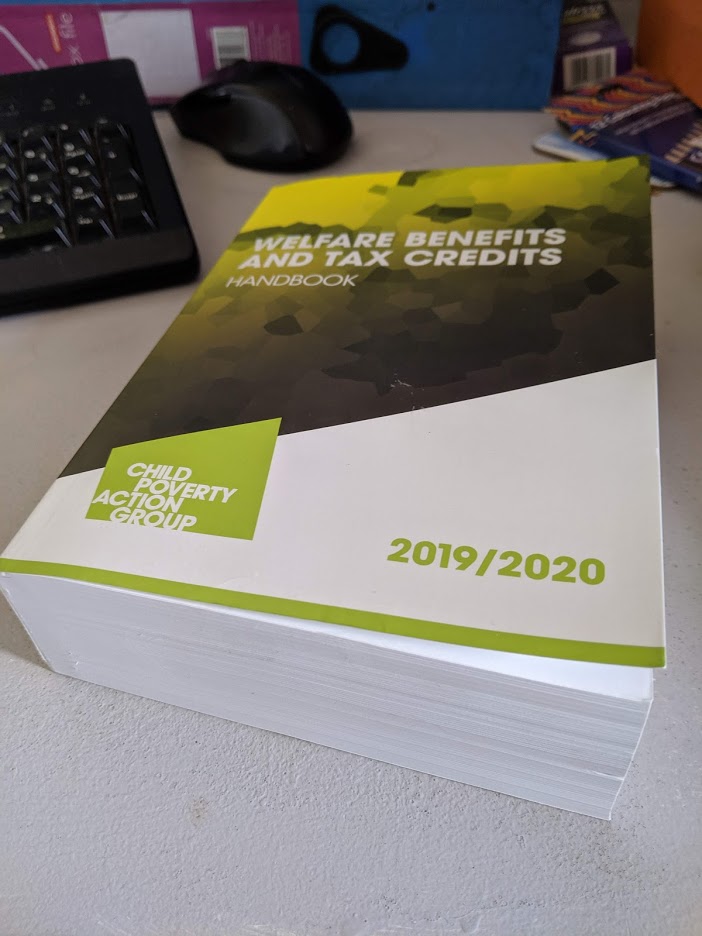

The corresponding thing for the Benefit System is the Child Poverty Action Group Welfare Benefits guide5, which looks like this^FN_MELVILLE]:

(Source: author’s photograph.)

(Source: author’s photograph.)

There is no royal road to creating the actual calculations; it’s mostly a question of judgement - how much detail it’s necessary to include, how best to use the available data, and so on.

Here’s a simple flowchart of the steps the model goes through:

Most of the steps here are hopefully familiar to you from earlier in the week; the one thing we haven’t discussed is uprating: our datasets are typically 1-3 years old by the time they are released and wages, prices and interest rates will have changed since the time of the interviews, so we multiply incomes, rents and consumption by amounts to reflect these changes.

How do we know the model is right?

A model of this sort inevitably gets quite big, and so there are lots of places it could go wrong. The model can be checked from the bottom-up: are the individual calculations are correct, is the survey data is handled correctly, and so on. Or it can be tested top down: are the models predictions for total amounts spent on benefits or raised in taxes close to what actually happens? In principle these two approaches are complimentary, but, as you’ll see, a model that is accurate at the micro-level might actually be quite bad at predicting aggregates, and good performance at the aggregate level might hide significant errors in individual calculations.

Bezanson, J., A. Edelman, S. Karpinski, and V. Shah. “Julia - A Fresh Approach to Numerical Computing.” SIAM Review 59, no. 1 (January 2017): 65–98. https://doi.org/10.1137/141000671.

Group, Child Poverty Action. Welfare Benefits & Tax Credits Handbook, 2019/20. CPAG, 2019.

Neidle, Dan. “Excitingly, My New UK Tax Books Have Arrived. 25,228 Pages. Jumbo Jet Shown for Scale.” December 2017. https://twitter.com/DanNeidle/status/941297373967454214?s=20.

Redson, Anne. Tolley’s Yellow Tax Handbook 2019-20. London: Tolley, 2019. https://store.lexisnexis.co.uk/products/tolleys-yellow-tax-handbook-201920-skuuksku9781474311069BYTH682579/details.

Stark, Graham. “Grahamstark/Stb.jl,” October 2019. https://github.com/grahamstark/stb.jl.